The Moonstone has been on the Lifeline ensemble’s list of must-do titles for years and years. It’s such a great read, such an important piece of the history of the genre, and such a well-written, well-crafted tale, that we all knew it had appear on our stage before long. We all loved the book, and we felt strongly that it would appeal to many of our loyal audience members, the mystery fans and period drama enthusiasts alike. After years of trying to figure out who specifically was going to tackle the mammoth project, back in 2007 (before The Island of Dr. Moreau had even completed its run) Paul and I stepped up and committed ourselves to being the team that would take it on. It wasn’t able to fall in our 2008-2009 season, because Frances was already at work on Busman’s Honeymoon, the final chapter in the Lord Peter Wimsey series, for that year. The ensemble slated the production to be the final show of our 2009-2010 season, but rights to produce Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere came our way unexpectedly in the eleventh hour, and Paul and I decided we needed to jump on that opportunity before it passed. The ensemble supported us and allowed us to push back The Moonstone to February of 2011.

So here we are, almost three years after Paul and I began our Moonstone conversations, two full in-house readings of various drafts behind us, the pre-production process trundling along, and only a matter of weeks before our full team gathers for the start of the rehearsal process. We’ve come a long way in the intervening time: our discussions have morphed from pie-in-the-sky, highly theoretical riffing and ramblings to super specific, nuts-‘n-bolts-y fussing over tiny details (where do we land for Cuff’s dialect?) and physical realities (where and how do we stage the trapdoor incursion of the Indians?) and challenging decisions (can we afford to lose the Yollands entirely?). I’m hard at work on what I’m calling my “third draft” (though, it’s really my sixth pass through the text), which is 16 characters, 77 pages, and 42,507 words shorter than where I started back in my very first draft, as I keep refining my vision, as I continue to focus on both clarity AND brevity (well, er, as close to “brevity” as an adaptation this sprawling could be said to be), and as Paul and I narrow further and further in on what the world of this production is going to be. And we’ve learned a lot as we’ve progressed.

The first major task was to identify the narrative framework we would use. I’ve done away with several of the less-essential narrators (the random Herncastle cousin, the steamboat captain, Cuff’s agent, etc), but have labored to keep as many of Collins’ wonderful crowd of voices present as possible. Direct address and the contrasting worldviews of the army of narrators are such important aspects of the novel, and I wanted them to remain intact in our stage production. And, actually, to give them a chance to come to LIFE in the hands of our wonderful cast.

Next, I had to wrestle with the broad structure of the piece. I’m not a big fan of intermissions in general, but the deeper I got into the work, the more a three-act structure for The Moonstone made the most sense to me. And now that we’re into our meetings with the design team, that structure is beginning to find conceptual support on the production end, and my worries about doing a two-intermission show are beginning to wane. A bit. =) We’ll see where we land by the time we get to opening.

The next round of editing was all about narrowing in on the character and plot elements that felt “essential” to me. I’ve kept as many of the characters and subplots as I feel the script can support, but fans of the novel will definitely miss some wonderful Collins creations like Superintendent Seegrave , Caroline Ablewhite, Gooseberry, and many more , as I’ve worked to wrangle a veritable army of fictional characters into fighting shape. Darlings had to be slain left and right. But many lovelies have survived to see the light of day.

Tone and style have been challenging issues to land on. There are as many different ideas about how this novel could be brought to the stage as there are members of Lifeline’s ensemble. Some see a highly presentational vaudeville of quick-cuts and zippy pace. Some imagine a broadly-drawn comedy of manners. One particular adaptor even envisioned it being set in a modern museum, with history-obsessed tour guides recreating the story for the benefit of the audience. These are all fascinating ideas and could each be fleshed out into interesting productions of their own, but they aren’t the direction Paul and I have grown excited to explore.

What fundamentally interests ME in the novel is a) the depth and breadth of all the many characters’ backstories (whether it be a “main” character like Franklin or Rachel, or a “secondary” character like, say, Jennings – who we don’t even meet until hundreds and hundreds of pages into the book), b) the depth and drama inherent in the many wonderfully complicated relationships (the masks that people wear, the lies and half-truths we tell, the confusion the truth can bring, the pain we can cause when we try to “protect” the ones we love), and c) the struggles of ALL of the characters to bring order and sense to an inherently chaotic and uncontrollable world (whether it be Clack with her religious tracts, Cuff with his theories, Murthwaite with his cultural analysis, Rachel with her silence, Franklin with his persistence, and on and on). Rather than just being a “mystery,” to me this story is a Drama (about relationships and the lies and misunderstandings that can threaten to tear them apart), which also happens to have a wonderful, weird, unusual Mystery wrapped up in it. It’s got all that refreshing depth of character that makes the Sayers mysteries so satisfying -- sure, the plot twists and turns are there, but they’re hanging on something deeper than stock characters and genre tropes.

So, Paul and I are eschewing a Moonstone of vaudeville or broad comedy and hoping to bring to life the truth behind all of these unusual, humorous, tragic, HUMAN characters. We’re going to explore the fears that drive them and the pasts that won’t release them. We’re going to tear the Verinder family apart and help them put the pieces of their lives back together -- those that survive, that is. Don’t worry: the fun of Miss Clack, Betteredge’s obsession with Robinson Crusoe, and all that great stuff will still be there, but so will the torments of Ezra Jennings, the trials of Rachel and Franklin, and the tragedy of Rosanna Spearman.

It’s all still very much in progress, still finding its feet, still moving slowly from the darkness to the light. And it’s been a challenging journey thusfar, though incredibly rewarding. And I look forward to sharing it with you in February.

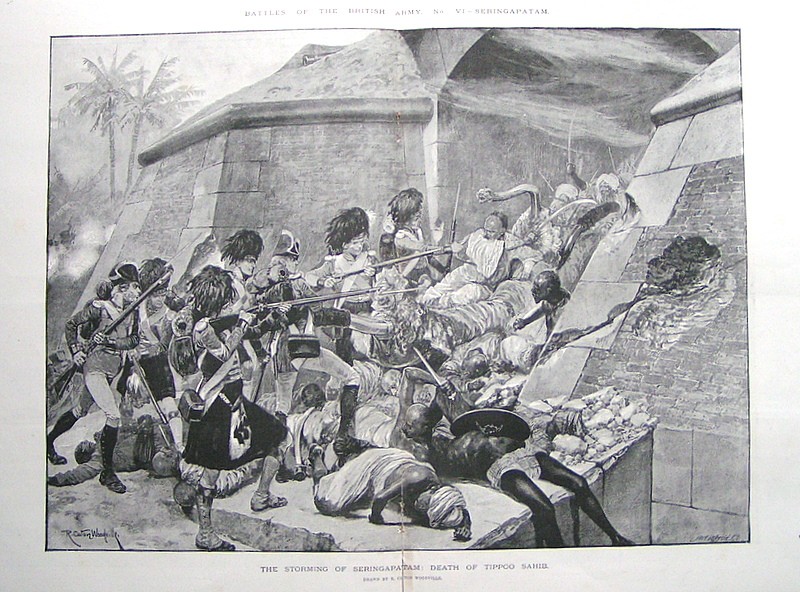

They tend to fall into four categories: focus on a woman or women (either in fancy dress or at the shivering sands), an exterior of a home or street(generally Gothic looking), the diamond, the Indians or an exoticized image of the god. In the case of older covers these foreign representations seem offensive and on one the quote from Dorothy L. Sayers is larger than Collins name.

They tend to fall into four categories: focus on a woman or women (either in fancy dress or at the shivering sands), an exterior of a home or street(generally Gothic looking), the diamond, the Indians or an exoticized image of the god. In the case of older covers these foreign representations seem offensive and on one the quote from Dorothy L. Sayers is larger than Collins name.